By Shicheng Huang

Often in data competitions, participants are given only a dataset and are encouraged to try to make predictions or carry out an analysis. In a real organization, doing data science also involves challenges beyond analyzing the data we are given. In this blog post, I will describe obstacles I faced when I tried to forecast a computer lab’s desktop usage.

Introduction:

I am part of the volunteer staff for the Open Computing Facility (OCF) at the University of California, Berkeley, where we provide free computer access to all students.

One project I worked on was to forecast our desktop usage (which I defined as the number of computers in use every minute during open hours) so students looking for a desktop can have an basic idea when the lab is busy.

Challenge 1: The data doesn’t exist.

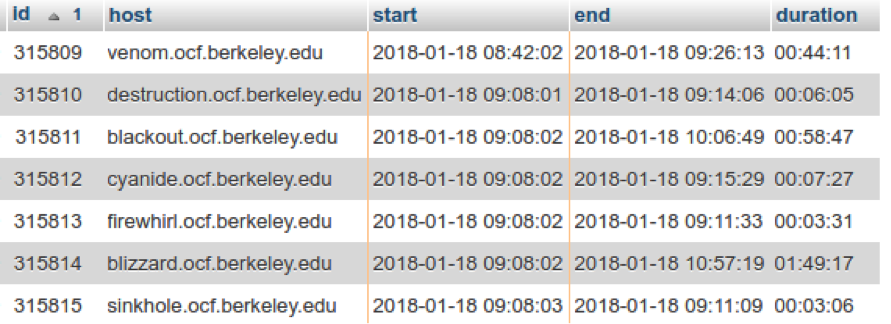

Ideally we want a data table that shows the number of desktops in use each minute. Instead, we have data for each desktop login session. Below is a snippet of the session database. Each row represents a user’s session. We have the times they logged in and out of the computer, and the “host” field identifies the name of the desktop.

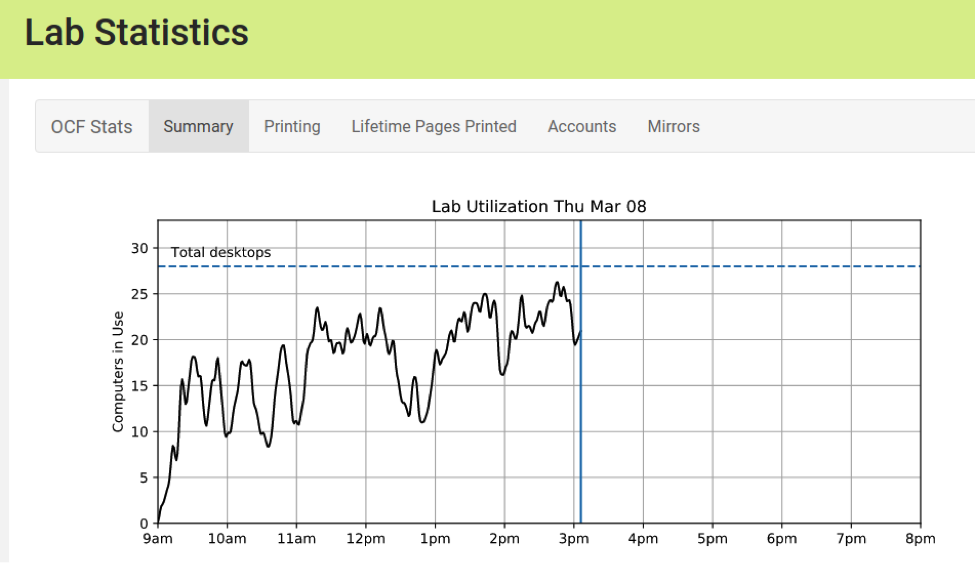

We have code to compute desktop usage from the session data. I ran this code and made a lab utilization graph (see figure below). This graph uncovered a problem with the data.

Challenge 2: The data is not accurate.

From my personal observations, the lab is often full during the afternoon, but the lab utilization graph rarely reached the maximum. The visualization contradicts my personal observation.

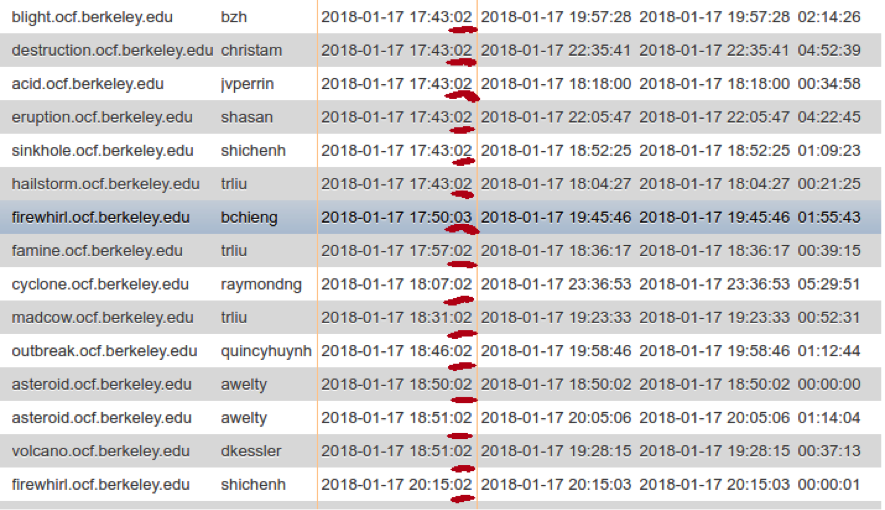

I asked a senior volunteer lab staff member how the data was generated. He directed me to the corresponding place in the OCF codebase and told me the session data was not accurate: all the sessions’ start times were mysteriously starting on the first 2 seconds of any minute (check figure below). The data had this oddity for several few months.

See most of the sessions start at “02.” and the first few session start at the exact same time, which is highly unlikely.

I reported this issue in our internal web forum and waited. Our deputy site manager responded that he found a bug in the code (the session tracking script). I asked him for more details in person, and he fixed the session tracking script. However, the new desktop usage graph on our website still rarely reached maximum utilization during the day.

I also found that the total number of desktops in the graph was wrong: the system was counting a desktop that was no longer in use. This time, our site manager corrected the corresponding records in our system. But still the utilization graph didn’t jibe with my experience in the lab.

Challenge 3: There is a limitation to what data can show you.

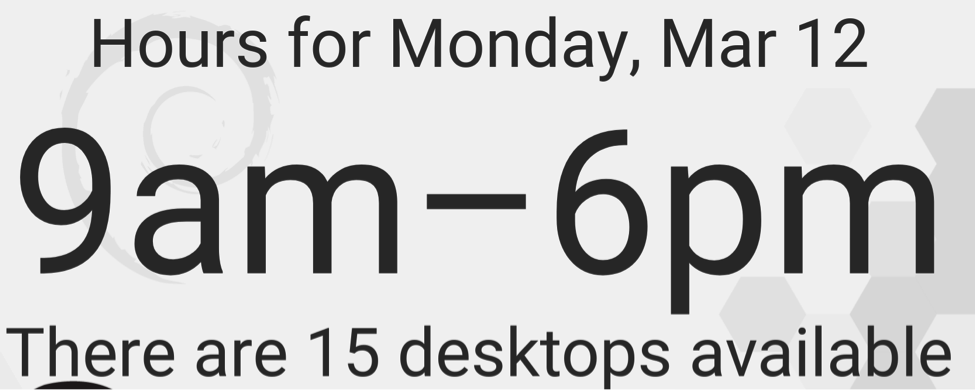

It wasn’t until I worked on another project that I the reasons for why the utilization graph was not “right.” My new project was to dynamically display the number of desktops available on the lab TV screen so that a user waiting in line can know in real time whether a desktop is available (see screenshot below).

One afternoon when the lab was full, the TV showed that the number of desktop available was, once again, not 0. So I walked around the lab and realized there were a few people occupying a desktop station who hadn’t logged into the desktop. Some of them did work on their laptops, and others were creating an OCF account to be able to log into a desktop. In short, we often have full lab utilization (all stations occupied) but not desktop utilization (all desktops in use).

Conclusion:

Here are some things I learned while working with data in a relatively small organization:

-

Data quality is important, and to check quality, data documentation is necessary. In my case, we discovered problems in how the data were processed and let staff know about these issues. The discrepancy between the data and the staff description led to the discovery of bugs in the script that generated the data.

-

It is nice if you have good engineering skills, otherwise you have to rely on communication with data engineers to work with the data pipelines. In my case, I was lucky to have been able to talk to the site managers and more senior staff to learn how the data was collected and correct any inconsistencies. But I had to wait for them to fix these problems. If I had the scripts and raw data available, I would have been able to uncover (and fix) the data problems myself.

-

Digital data is often not enough; you need to gather as much supplemental and contextual information as possible. In my case, I have lots of knowledge about the lab since I am physically in the lab for a long time. And this knowledge led to the discovery that the data were not capturing the actual situation of fully occupied stations and under-utilized desktops.

References

https://towardsdatascience.com/the-ten-fallacies-of-data-science-9b2af78a1862

https://www.slideshare.net/ChuongTomDo/data-products-in-the-real-world-why-predictive-performance-is-the-least-of-your-problems